Sound can tell us many stories as it changes over time. The evolution of a single unaccompanied frequency over time is what we commonly refer to as a Melody, when two or more frequencies progress through a ever changing tapestry of tension and resolution. When two or more frequencies occur at the same time we refer to this as Harmony.

Sound is the sonic product of physical objects vibrating.

Music is sound that is given rhythm, structure and form.

Pitches are regular repeating frequencies of vibration.

The faster the vibration, the higher the pitch.

The slower the vibration, the lower the pitch.

Notes are names that we give to specific pitches.

When a frequency is doubled, we give it the same name.

When a frequency is halved, we give it the same name.

This happens in infinity, but our ears have natural hearing limits, from around 20 vibrations per second to around 20,000 vibrations per second. Within this range we find our musical language.

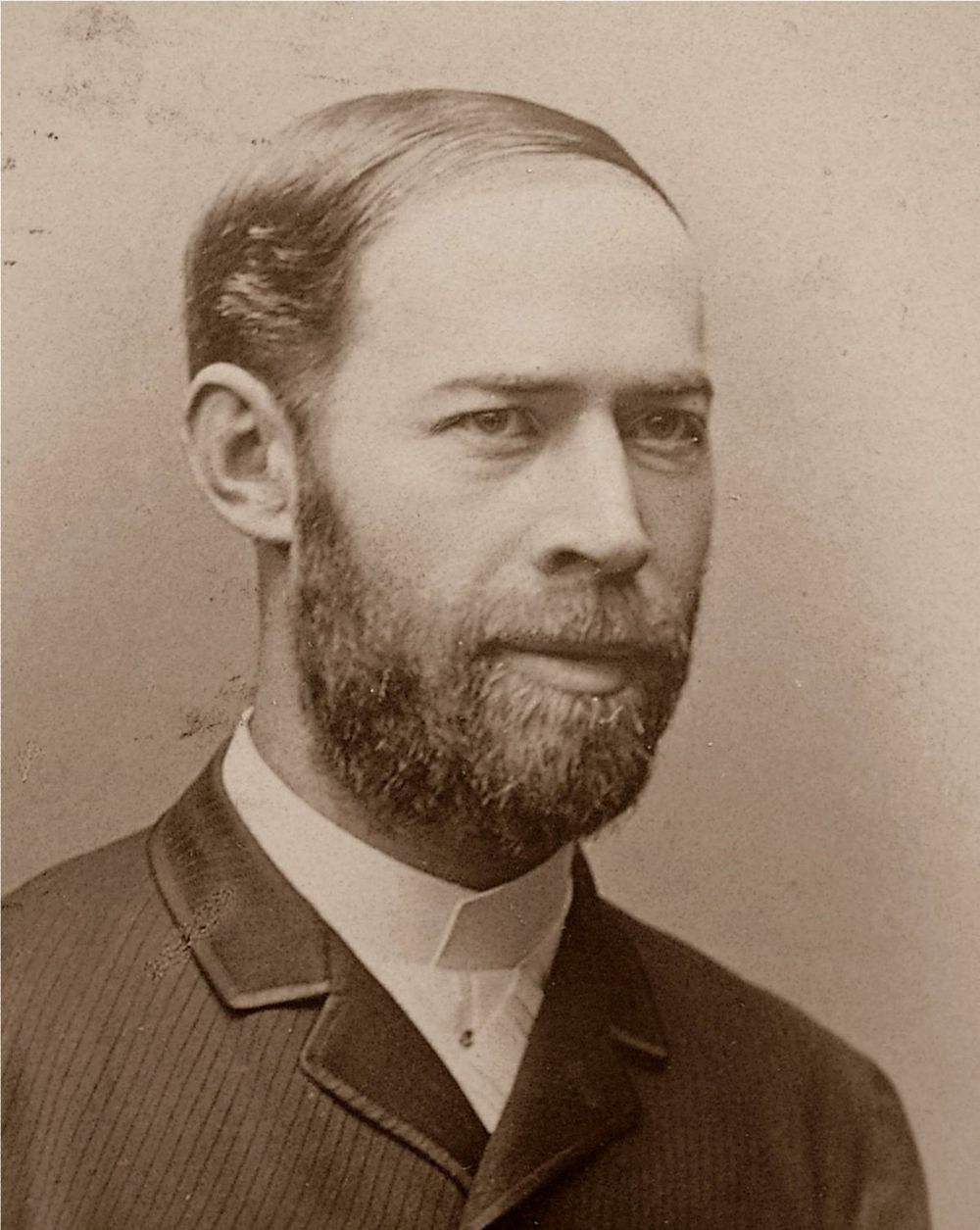

We commonly refer to the concept of “vibrations per second” as “Hertz”, or shortened to “Hz”, named after the German scientist who discovered this phenomenon, Heinrich Hertz.

Dis Guy! 👆🏻

There are a few important concepts to understand when we start trying to wrap our heads around how the musical piano keyboard is laid out.

But before we learn our ABCeeez, some words from our sponsor:

Syntorial

Learn MoreThank you, and now back to our content...

Frequencies

Imagine sitting down at a piano and your friend asks you to play the frequencies:

“262Hz, 330Hz, aaaaaaaand… 392Hz…ready, go!”

…well…

…um…

…this kind of situation miiiiight be a bit off putting, to say the least. How is one supposed to know which keys on the keyboard represent those frequencies? We could memorize them…all 88 of them…on a piano keyboard…and they would all be completely different and unique, but that is quite a lot of memorization, and it would still be very difficult for the human mind to recal any individual piano key quickly in the heat of the moment.

…So, what do we do?

Notes

Turns out, there are some rather handy patterns in the distribution of frequencies accross a piano keyboard, if we just look for them. The most important pattern is that of Doubling.

If one studies the frequencies of notes on a piano keyboard, one will notice that after 12 notes, the next note is a doubling of the first note. Thae a look at this:

- 262Hz

- 277Hz

- 293Hz

- 311Hz

- 330Hz

- 349Hz

- 370Hz

- 392Hz

- 415Hz

- 440Hz

- 466Hz

- 494Hz

- 523Hz

You will notice that the 13th note in this sequence is essentially double the frequency of the first note. I say ‘essentially’ because it is not an exact doubling, but ‘close enough’, which will open up a big discussion in regards to tuning systems, which can be duscussed another day. But ultimately, to the hunam ear, at least, they will sound very similar to each other, although one will be significantly higher in pitch. This pattern will continue up and down the keyboard for all notes, where every 13th note is a doubling. This leads us to an important concept, which is that of Equivalence.

Equivalence

Equivalence

noun

The condition of being equal in value, worth, function.

This word means that two or more things are more similar than they are different, to the point that in the context of the piano keyboard we can basiclaly think of them as the same thing, or functioning in the same way. And this leads us to very important idea, and that is or repetition of names.

Because 262Hz and 523Hz are roughly the same in function, we can name them the same thing, and this is how we get to the idea of Note Names. Because we can do this with all of the notes on the keyboard, so instead of having to memorize 88 different freqenices and their corresponding keys on the piano keyboard, we simply need to memorize 12 note names and their visual position relative to each other, which then repeats up and down the keyboard from bottom to top and top to bottom.

Since every 13th note is essentially a doubling of frequency, we can take a look at that on a keyboard:

MIDI

C

C

C

C

C

C

C

C

This is very useful because we can start to see a pattern emerge. If we look at the black keys we notice that the note that we are currently calling “C” is to the left of each grouping of two black keys. Because all of the “C” notes share functional equivalence we can refer to them in the same way. The name for this is called a “Pitch Class”.

Pitch Classes

All of the notes on the piano keyboard that are doublings of each other are considered to be in the same Pitch Class and we refer to all of the notes in the same pitch class by the same letter name. In the previous example, that name is “C”, but every pitch class has a designated name. In music we use the first seven letters of the english alphabet to designate the seven White Keys before the pitch class repeats itself. The Black Keys use the names of the surrounding white keys plus an added symbol for their names.

…but why…the word “Note”?

Note

noun

A brief record of facts, topics, or thoughts, written down as an aid to memory.

Well, the word “note” means to write down for later, to remember, to keep track of, to save, so in this case, we are saving a series of names for each frequency on the keyboard that are hopefully very easy to remember and help to greatly simplify our understanding of the layout of a piano keyboard. This makes them very useful to us and will aid in our understanding of more complex musical relationships in the future.

Alright then, onward…

So, now that we have a better understanding of how note names work, let’s start learning the layout of the keyboard.

The Keyboard

The keyboard has 12 notes that repeat themselves up and down the range of the instrument. These 12 notes are laid out in an asymmetrical repeating pattern of black and white notes that is designed to make it easy to see and to feel every note as simply and quickly as possible. This asymmetrical pattern can be split into two Zones.

Two Zones

MIDI

Zone 1

Zone 2

MIDI

Zone 1

The first “zone” on a keyboard is commonly referred to as Zone 1. It consists of three White Keys and two Black Keys.

MIDI

Zone 2

The second “zone” on a keyboard is commonly referred to as Zone 2. It consists of four White Keys and three Black Keys.

When we combine the zones together we get all 12 notes of the western musical scale.

MIDI

Zone 1 + Zone 2

You will hopefully notice that the two zones combined create what is referred to as an asymmetrical layout, meaning that the two zones are not the same.

…but…why?

Well, the basic idea is that an asymmetrical layout allows players to find notes as fast as possible, and with multiple senses. If the keyboard layout were symmetrical, for example, one white key nad one black key repeating, it would be difficult to locate notes by sight very quickly, as their is no visual indicator to signal the position of one note from another, and completely impossible to locate notes by touch…

…by…touch?

Why, yes :-) You see, it is often the case that piano players play notes and chords and all sorts of things without even looking at the keyboard at all. The asymmetrical layout allows this to be even possible at all, by ensuring that every note has a unique physical position on the keyboard, which can be found with only touch.

Try it yourself. Close your eyes and feel the keys on your keyboard. Now, try to locate zone 1 by feeling for the two black keys clustered together. If you feel three black keys, then you have found zone 2. After you have found zone 1, feel for the white key to the left of the two black keys and play and hold it. Now open your eyes and see what you played…

…it should be C!

The concept behind this layout is to help us find any note on the keyboard as fast as possible. If we were to divide the12 notes in half we would get 6 and 6. But if we laid out the notes alternating between white and black keys, it would be hard to find any one pitch. By dividing 12 into odd numbers of 5 and 7, and then dividing 5 into 2 and 3, we end up creating an asymmetrical pattern that allows each white key to have it’s own unique position against the black keys that can be seen instantly.

The White Keys

The white notes on a piano keyboard are named using the first 7 letters of the english alphabet. These 7 letters correspond to the 7 white notes across zones 1 and 2 combined, although we start with the letter C, instead of A, cuz reasons…which we will get to later.

MIDI

Zone 1

C

D

E

Zone 2

F

G

A

B

Zone 1 + Zone 2

C

D

E

F

G

A

B

White Key Chart

To help memorize the position of the notes, we can break each notes position down to its physical relationship to the black keys. Each of the 7 white keys has a unique position that repeats itself up and down the full range of the keyboard.

MIDI

C

D

E

F

G

A

B

You can use any acronym or memory device that you want to help you remember each white notes position in relationship to the black keys, but my personal technique is to describe each notes position in words.

- Cis to the left of the 2 black keys

- Dis in between the 2 black keys

- Eis to the right of the 2 black keys

- Fis to the left of the 3 black keys

- Gis the left note in between the 3 black keys

- Ais the right note in between the 3 black keys

- Bis to the right of the 3 black keys

So every note to the left of the 2 black keys will be C, every note in the middle of the 2 black keys will be D, and so on. Practice finding one note at a time, up and down the full range of your keyboard. No matter the size of your board, this will always be true.

Let’s shorten these down even further to make them more memorable. This may seem like a trivial step, but it will help your memory retention immensely:

- Cleft of the 2

- Dbetween the 2

- Eright of the 2

- Fleft of the 3

- Gleft between the 3

- Aright between the 3

- Bright of the 3

Mnemonics

This kind of thing is called a Mnemonic. It’s a strange word, as it has a silent M at the beginning. But a Mnemonic is a mental device such as a pattern of letters, ideas, or associations that assist in remembering something. Mnemonics can be anything really, so long as they asist in the learning and memorizing of some piece, or pieces, of information.

The Black Notes

The black notes are named after the white notes, with an added alteration. We use the Sharp (#) and Flat (b) symbols to name each black note based on the 2 white notes that surround it. The sharp (#) sign is used when moving to the right, or up the keyboard (in pitch). The flat (b) sign is used when moving to the left, or down the keyboard (in pitch).

MIDI

Zone 1

C#

Db

D#

Eb

Zone 2

F#

Gb

G#

Ab

A#

Bb

Zone 1 + Zone 2

C#

Db

D#

Eb

F#

Gb

G#

Ab

A#

Bb

In Practice, we only use one of the two names at a time, based on it’s context. This may seem a little strange at first, but it won’t be long until you become comfortable with it. This concept has a name of course, as all things in music theory generally do.

Enharmonics

A note is a singular frequency (with overtones, of course :-), and no matter what we call that note, it will always be the same frequency. But because the context with which a note is referenced can change, we often end up having multiple names for notes. In fact, every note on the piano keyboard has at least two notes, if not more.

We consider these multiple note names for the same note as being enharmonically equivalent.

This means that any and all names for the same note are considered equal, as they are referencing the same underlying pitch. In the case of the black keys they don’t actually have note names of themselves, and instead rely on the white notes around them to recieve a name. So, in general, we refer to this concept as Enharmonics.

MIDI

In this example the white note to the left of the black key is C, so we name the black key C#, as this is the context with which we are referencing this note.

C

C#

MIDI

In this example the white note to the right of the black key is D, so we name the black key Db, as this is the context with which we are referencing this note.

D

Db

Both of these notes are the same exact pitch, but we use either the sharp version or flat version depending on the context that we are referencing the note from. This idea of Enharmonics will surface again and again, even with the white keys, so it’s important that we become familiar with it from the beginning, or else it will end up being an annoying and confusing thought that creeps into our music at unwelcome moments in the future.

Black Key Chart

Here are all the black keys and their associated names in each zone on the piano keyboard. Attempt to become as familiar with these notes as you endevour to become with the white notes, as your music will suffer greatly if you ignore them of otherwise relegate them to your future. The best music uses all of the notes all of the time.

MIDI

C#

Db

D#

Eb

F#

Gb

G#

Ab

A#

Bb

Again, the best way to memorize the positions of the accidentals is to break them up into individual notes and practice finding each note, one at a time, up and down the range of the keyboard.

Musical Alphabet

When we finally combine all of the white and black notes together from both zones 1 and 2, we end up with the musical alphabet of tonal theory. These are the notes that we will use to compose everything, and it’s very important that we treat these notes and their associated names in the same way that we treat the letters of the alphabet of any language. These notes and their names need to feel as natural as breathing, because we are going to use them to tell our musical story, and if we are not fluent in themn then we will constantly stumble our way to an unrealized musical vision.

MIDI

Zone 1 + Zone 2

C

D

E

F

G

A

B

C#

Db

D#

Eb

F#

Gb

G#

Ab

A#

Bb

Here is a tool that will help you practice your recognition of the notes and speed up your memorization over time. When you click on a note name all of the associated notes on the piano will light up in a color of your choosing and you can then try to play them on your midi connected keyboard as well. Try to test yourself by picking a note in your mind, then play that note on the keyboard in every octave that your keyboard contains, then press that notes button to see if you were correct. If you do this for a few minutes everyday you will become familiar with these notes in very little time.

If you enjoyed this article and found it useful,

then please consider donating to support :-)

If you enjoyed this article and found it useful, then please consider donating to support :-)